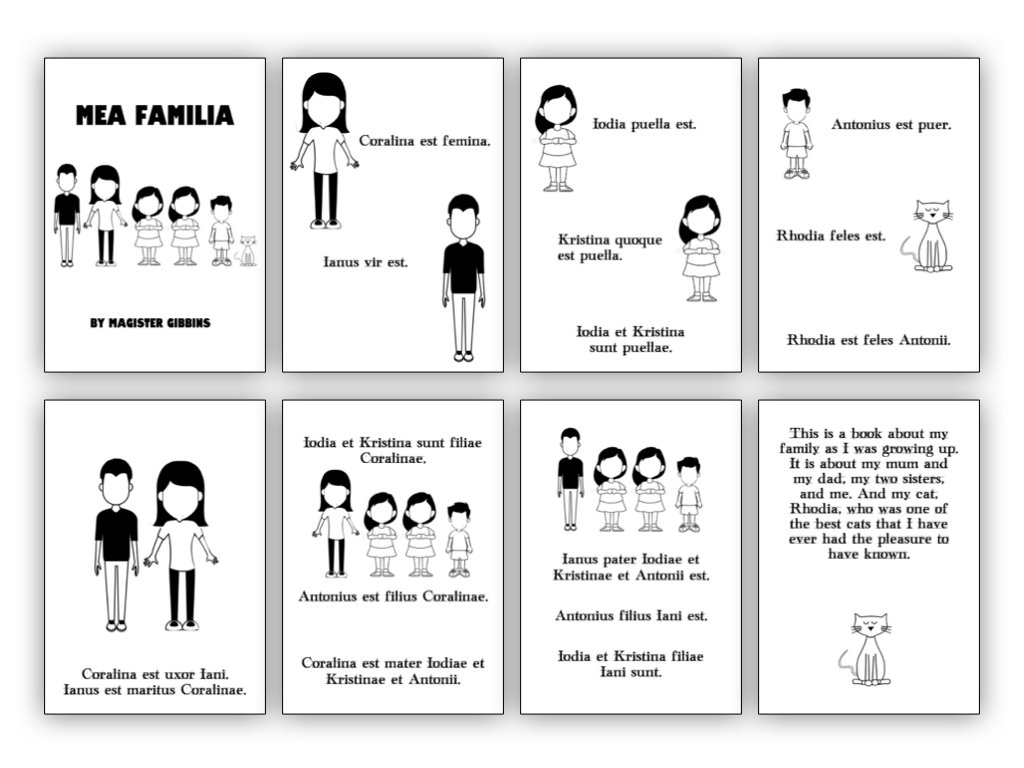

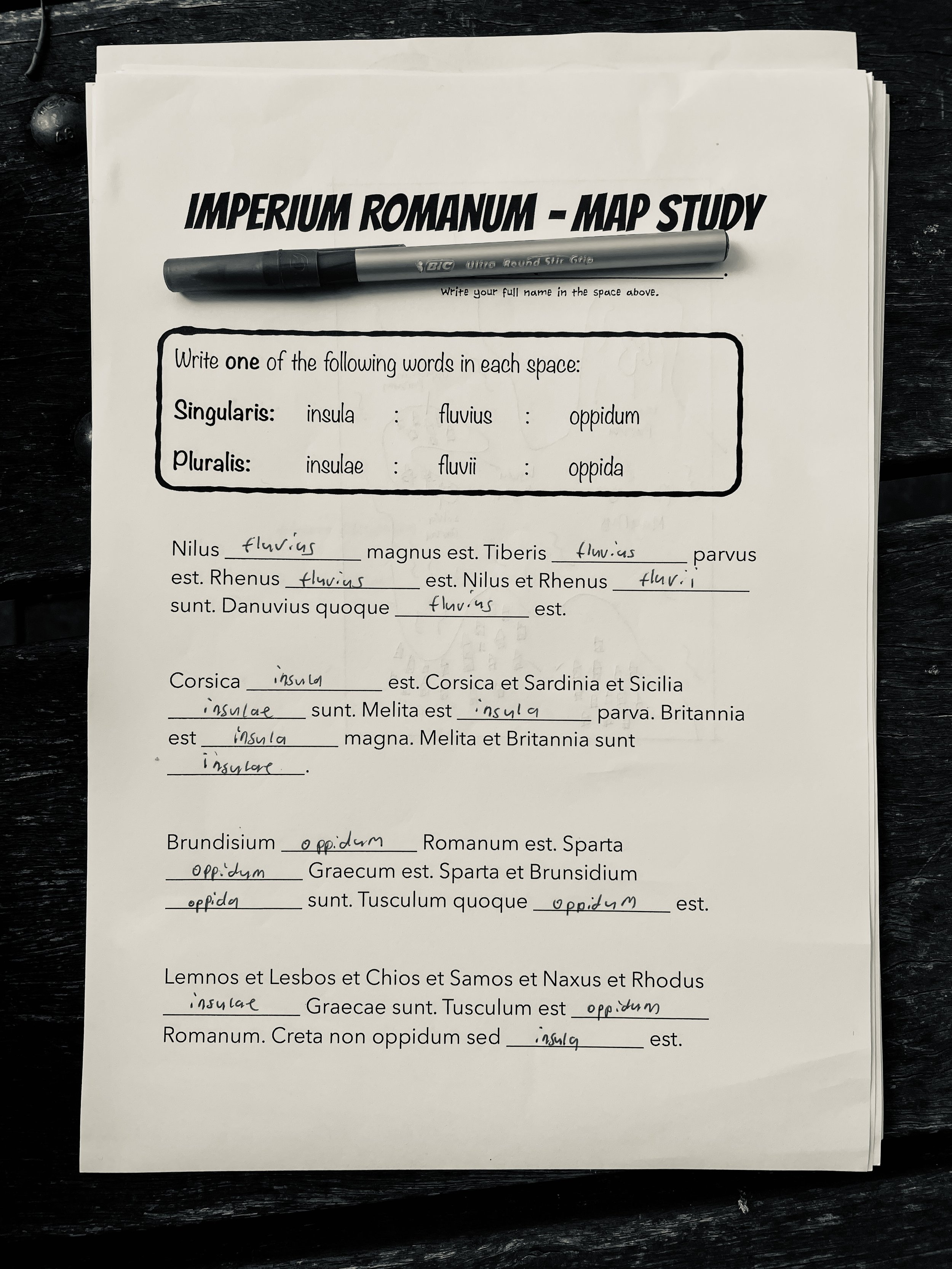

I began by reminding the students of our previous class test, and how they were given the paper to look at beforehand. I also reminded them of the last question of that test, in which they were asked to write a description of an imaginary island. I told them that for this test, they would only be given two questions in advance, and handed out one of those questions to them now. Note: For the sake of reducing paper, the second question was printed on the back, but I told them to ignore that for now. Class test can be downloaded here.

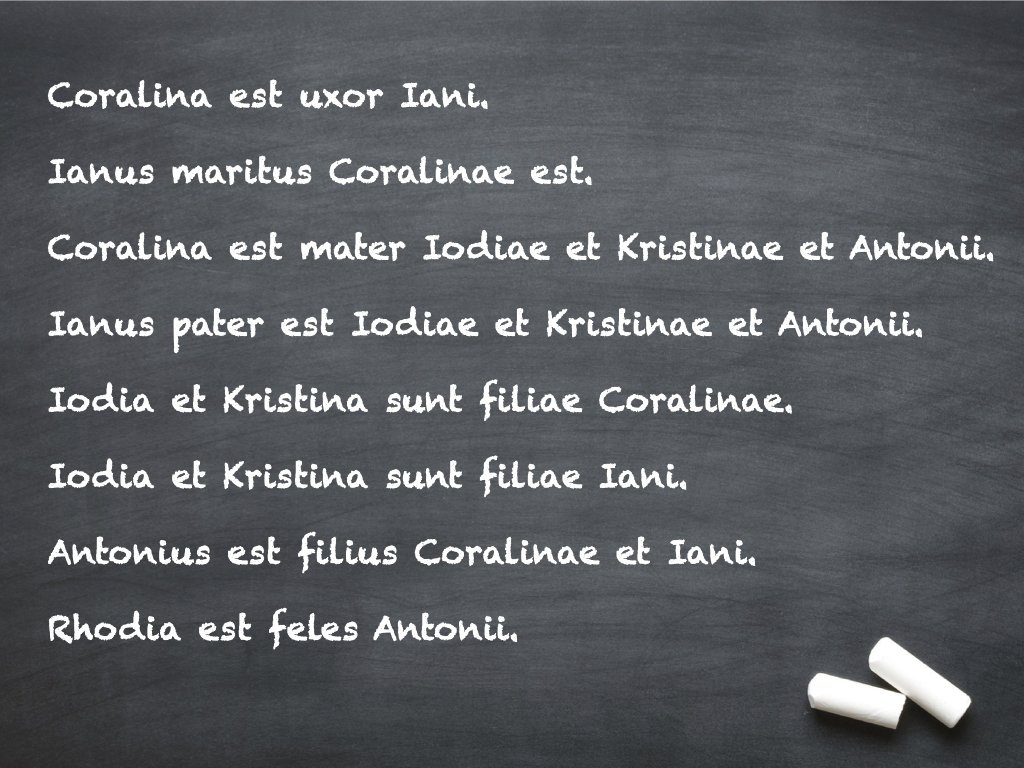

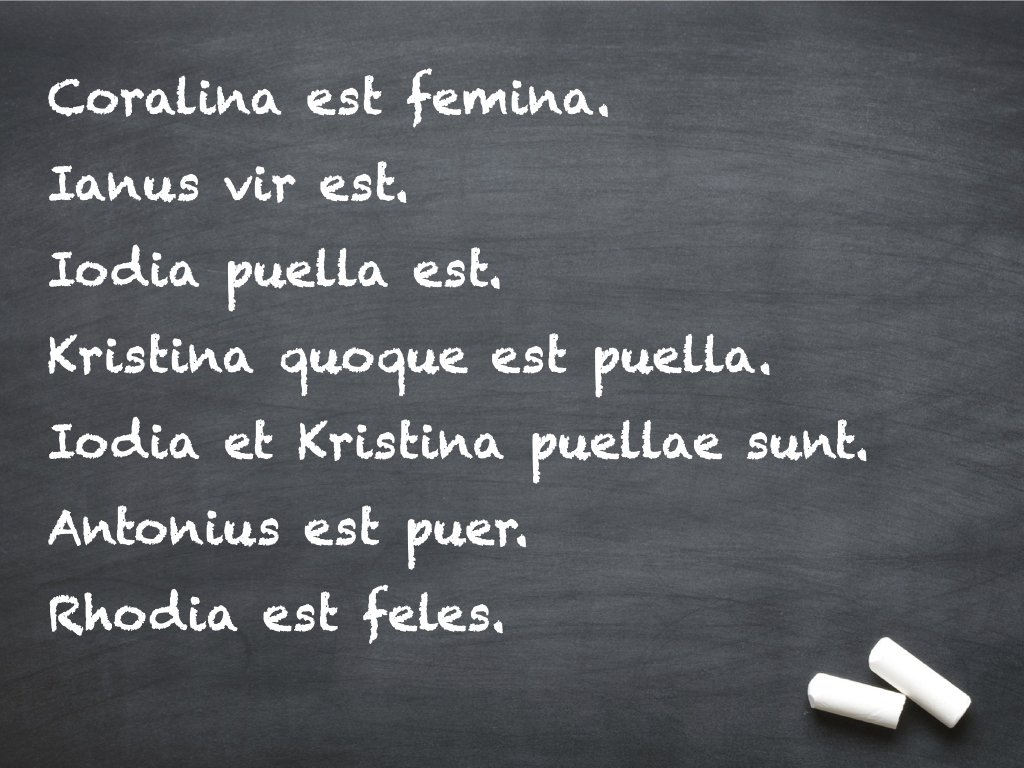

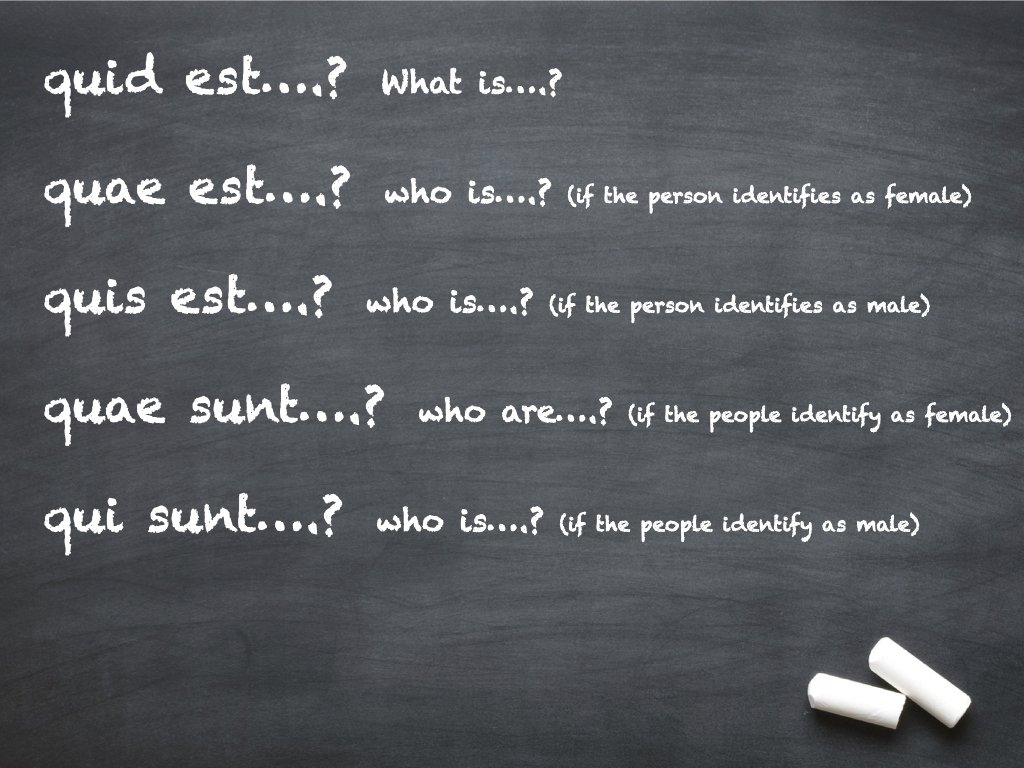

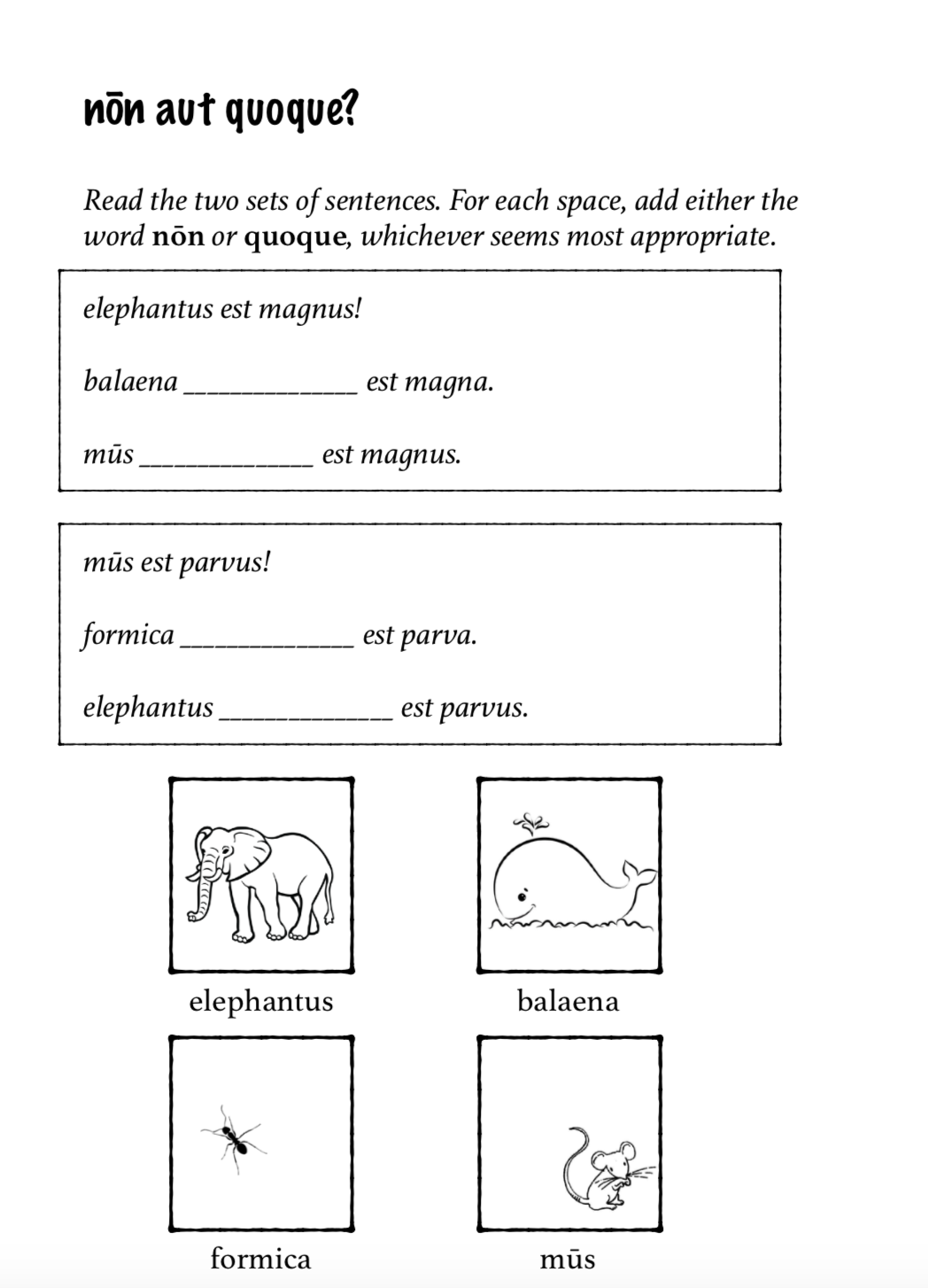

2. I asked the students to suggest a few sentences that they might write in response to the above question. This led to a discussion about how to tell and man from a women, a child from from an adult, a girl from a boy. Other students offered answers about the name endings, and the layout of a family tree.

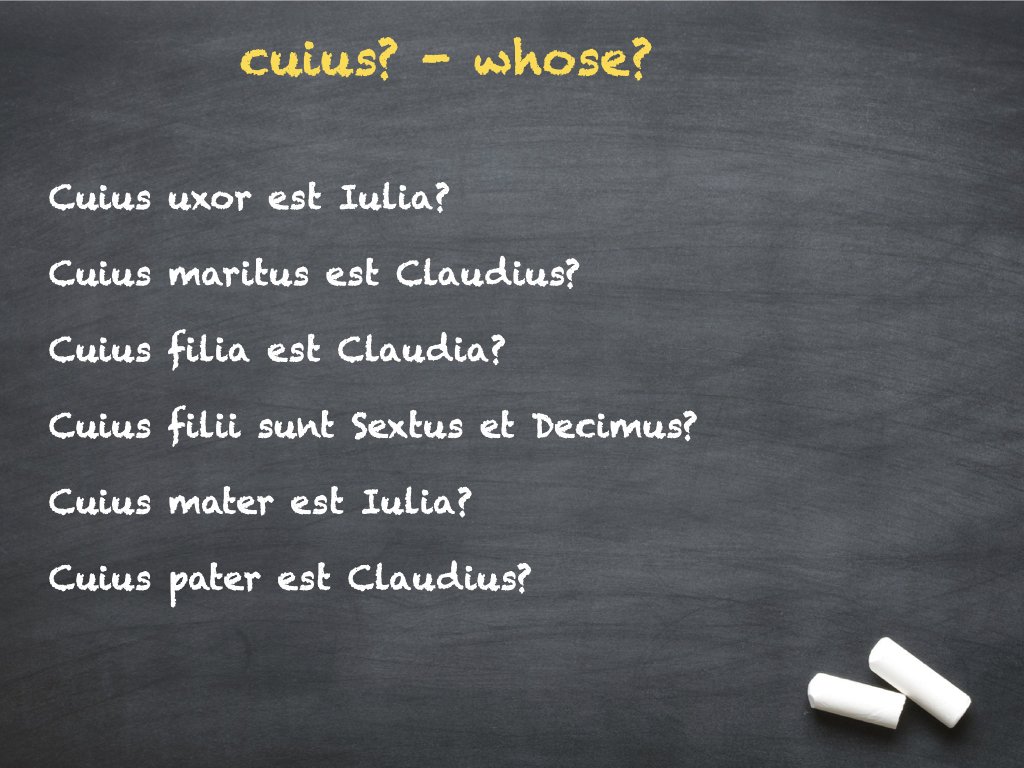

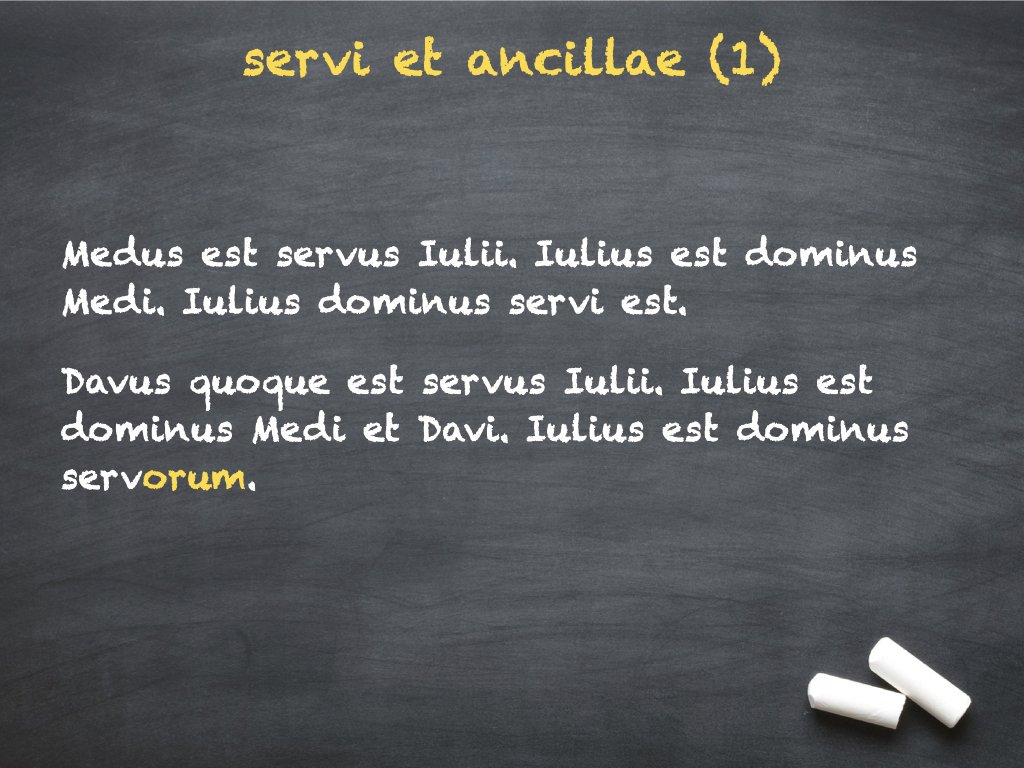

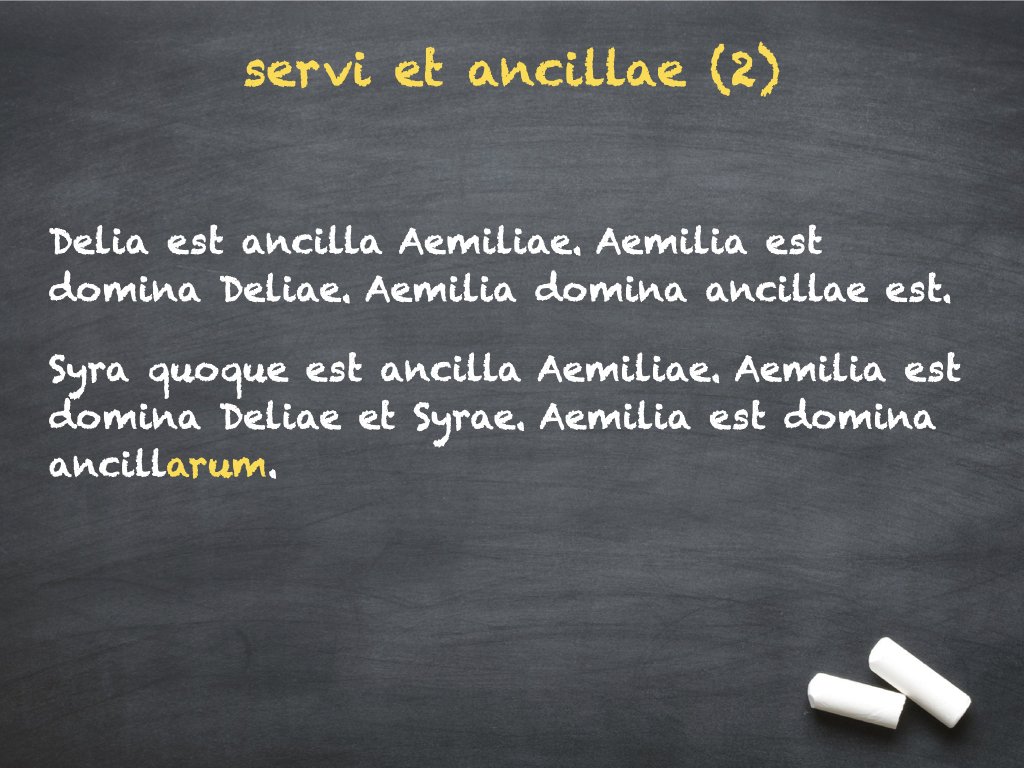

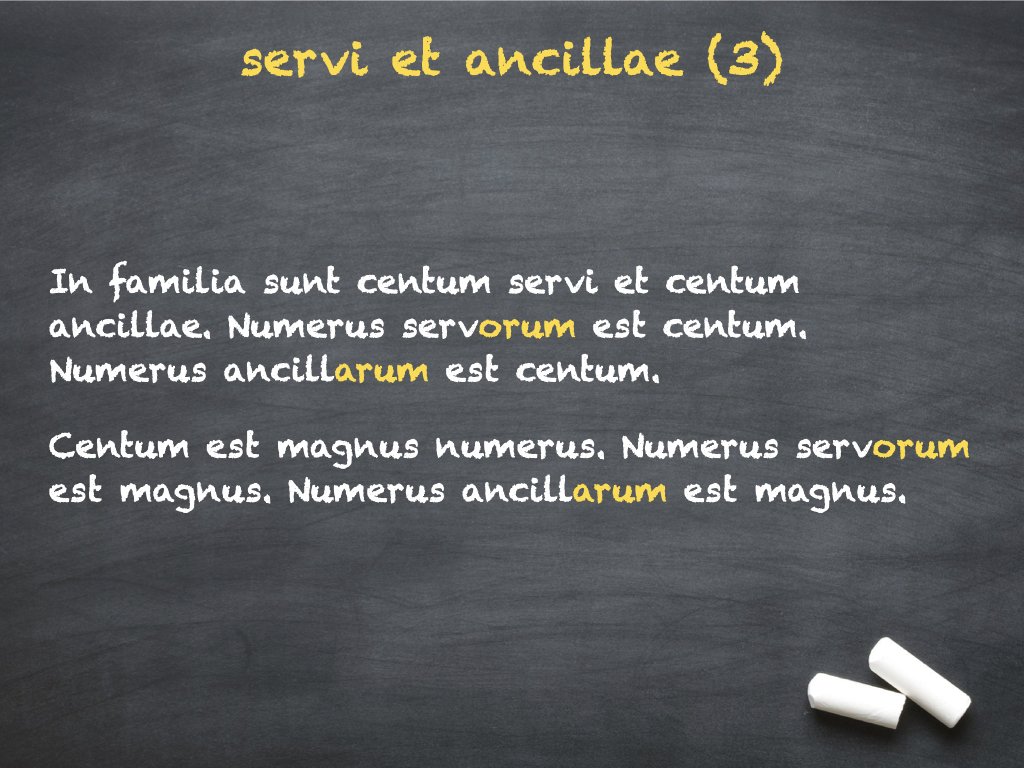

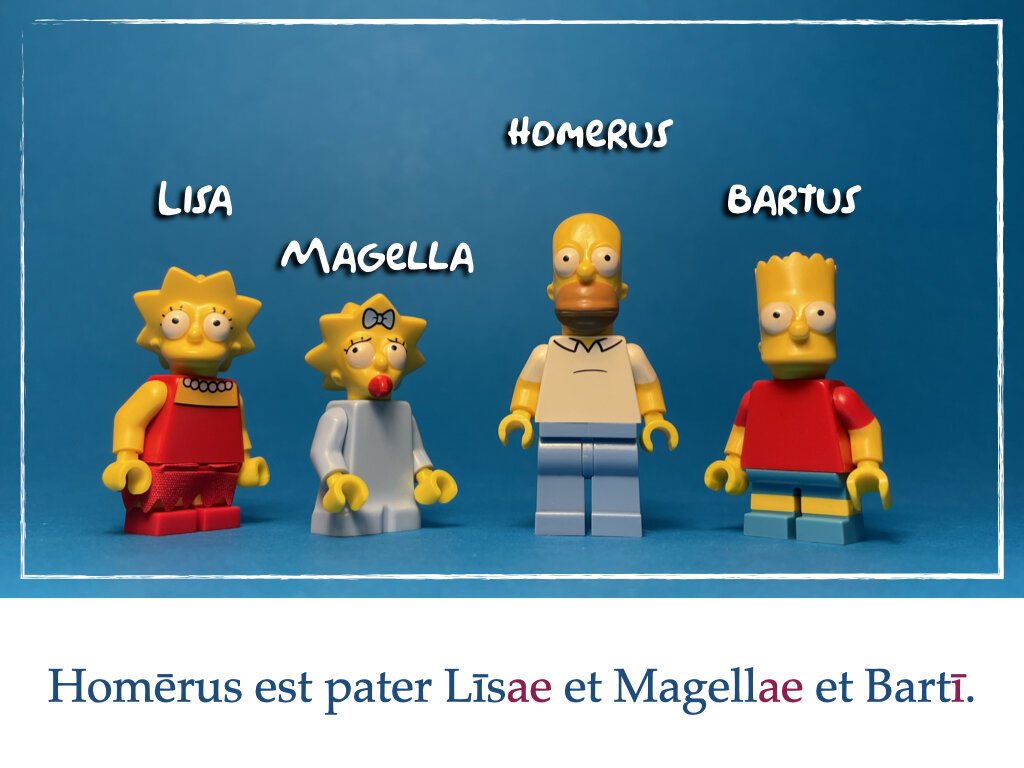

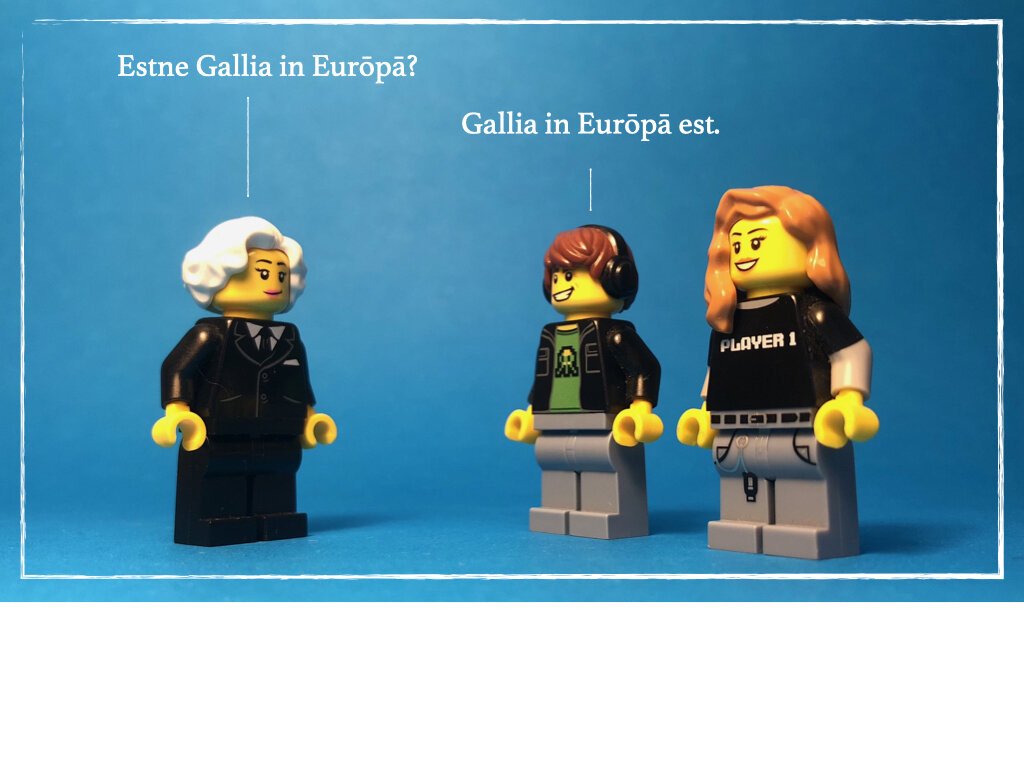

3. I wrote a heading on the board, and asked the students to copy it into their book, explaining that the title gave the English meaning of a new Latin word. I asked them to copy down and respond to a series of question, using the family to tree to find their answers. Note: I told them that any of the sentences they (correctly) write while responding to these questions would be appropriate in the upcoming class test.

4. The students worked on these, while I made myself available to answer their questions. Some students were unsure which words needed to be put into the possessive form, but for most of these the activity itself seemed to bring some clarity. For a portion of this group, there is still a level of uncertainty.

5. We finished the activity, and the lesson, by going through possible answers to the question. Along with individual words, students wanted to test the order of the words they used. There was considerable variety.