We began with our formal greeting (see Lesson 1). From now on I won’t mention this again, unless I am using it to explain a new point of grammar. But we will continue to do this greeting at the beginning of each lesson, as a way of showing the students the power of the imperative.

The students took out the maps that they had drawn for homework (see Lesson 2) and showed them to their friends. They were instructed to ask each other about individual features on the map by pointing at each and asking “Quid est?”. The possible responses were written on the board; “insula est.”, “silva est.” etc. I encouraged them to write “HIC SUNT DRACONES” (Here be dragons) in the corners of their maps. I asked them to keep the maps safe for our next lesson.

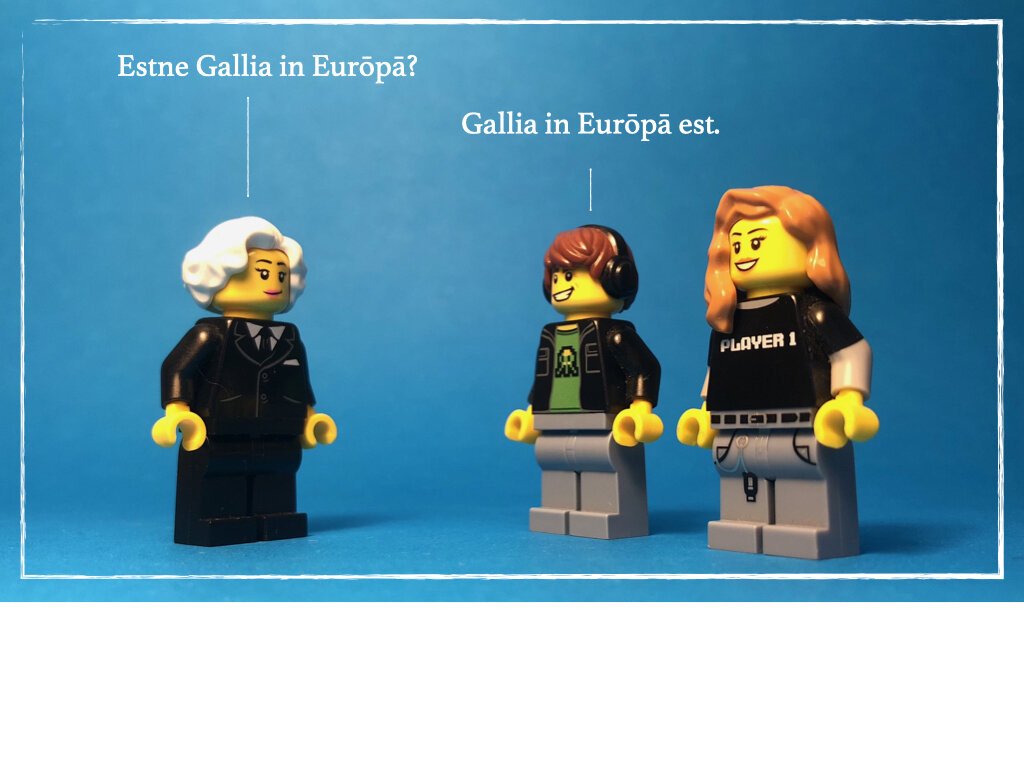

3. I reminded the students of the two questions, estne? and suntne? and the responses sic and minime. I then asked them to open their texts to page 6 (the map) and respond to a series of quickly asked questions. They were along the lines of ‘estne Germania in Europa?’, ‘suntne Corsica et Sardinia fluvii?’. I asked probably twenty questions, with the class responding ‘sic’ or ‘minime’ to each in unison.

4. I now wrote the following sentences on the board. Nilus est fluvius magnus. Rhenus et Danuvius sunt fluvii magni. Tiberis fluvius parvus in Italia est. I asked them to locate these rivers on the map (they are each mentioned in the first 21 lines of Capitulum Primum.).

5. I held up the LLPSI book and showed the students our plan for the year, that we intend to read though 5 chapters in the first half of the year, and another 5 in the second half. I explained that if they continued with Latin, this would be their book for at least another two years.

I explained that the book is written in such a way, that often the meaning of a word can be guessed from the book itself. As an example, I wrote up “sunt multi fluvii magni in Europa.” I asked the students to write down what they thought might be an English equivalent for multi. Answers included multiple, many, several, more-than-one and lots. Nearly all of the students correctly deduced the meaning of the word.

6. I explained that we would now be reading the first 21 lines of our textbook. I said that there was one word that they would be meeting for the first time - ubi - and that as we read they should attempt to deduce an English equivalent of this word, writing it down in their books. 19/21 students correctly deduced ‘where’.

I displayed the first 21 lines as set of illustrated slides - you can find them here - on the board, and read the text aloud, pointing out features on the maps as I went. When we read the slides with the teacher and two adolescents, I had the students read out together the adolescents’ responses. (By the way, the teachers names a Phillipus and Livia, and the adolescents are Diana and Apollo - not the gods, by names after them. They are Phillip’s children.)

7. I next asked the students to reread through the same 21 lines from their text on their own. We set up a section at the back our books entitled - nondum intellego - I don’t yet understand - to write any words, phrases or sentences that they were unsure of. I gave them about ten minutes, and most read through it more than once. At the end, those who had recorded something shared them. The only words that caused any trouble were ‘quoque’ and ‘sunt’, and even these rarely caused an issue.

8. I had thought that the reading of the text would take longer than it did, so we had a spare ten minutes. I used this time to explain the remaining rules for Provincia, and announced that we would play next lesson. The full rules can be downloaded with the game, here, but I used a set of scoring rules that can be projected onto the screen, which you can access here. In describing the rules I was sure to use Latin terms among my English, for example: If you make a “silva parva” you get “unum punctum”, but if you make a “silva magna” you get “septem puncta”. If you build an average sized silva you get nihil, nothing at all.