Salvēte, sodālēs.

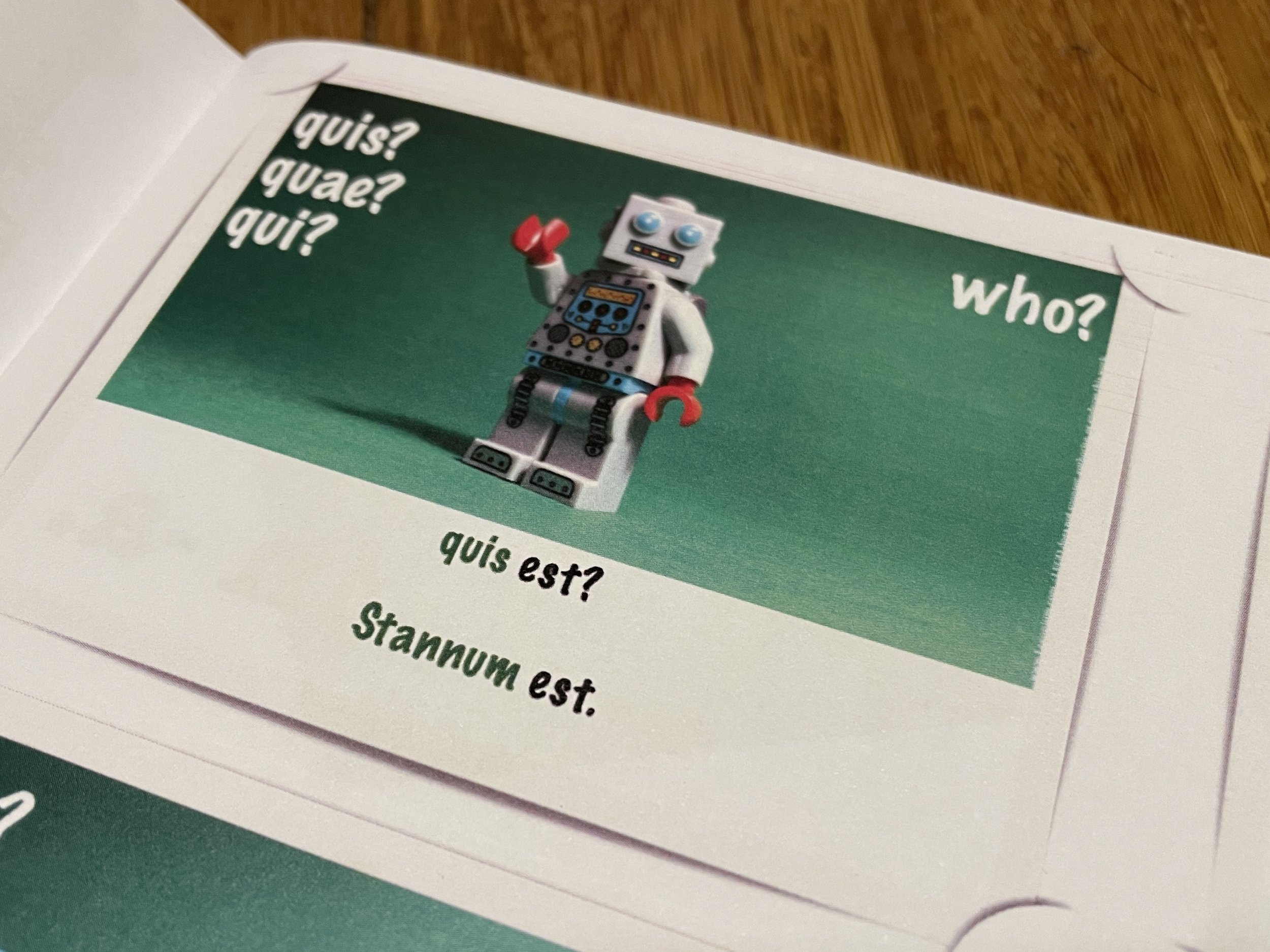

From Handy Latin Tables Pars Prima, page 8.

Just one new thing in today’s lesson - the word cuius (whose). And only two lines of Lingua Latīna Per Sē Illustrāta to read, lines 35-36.

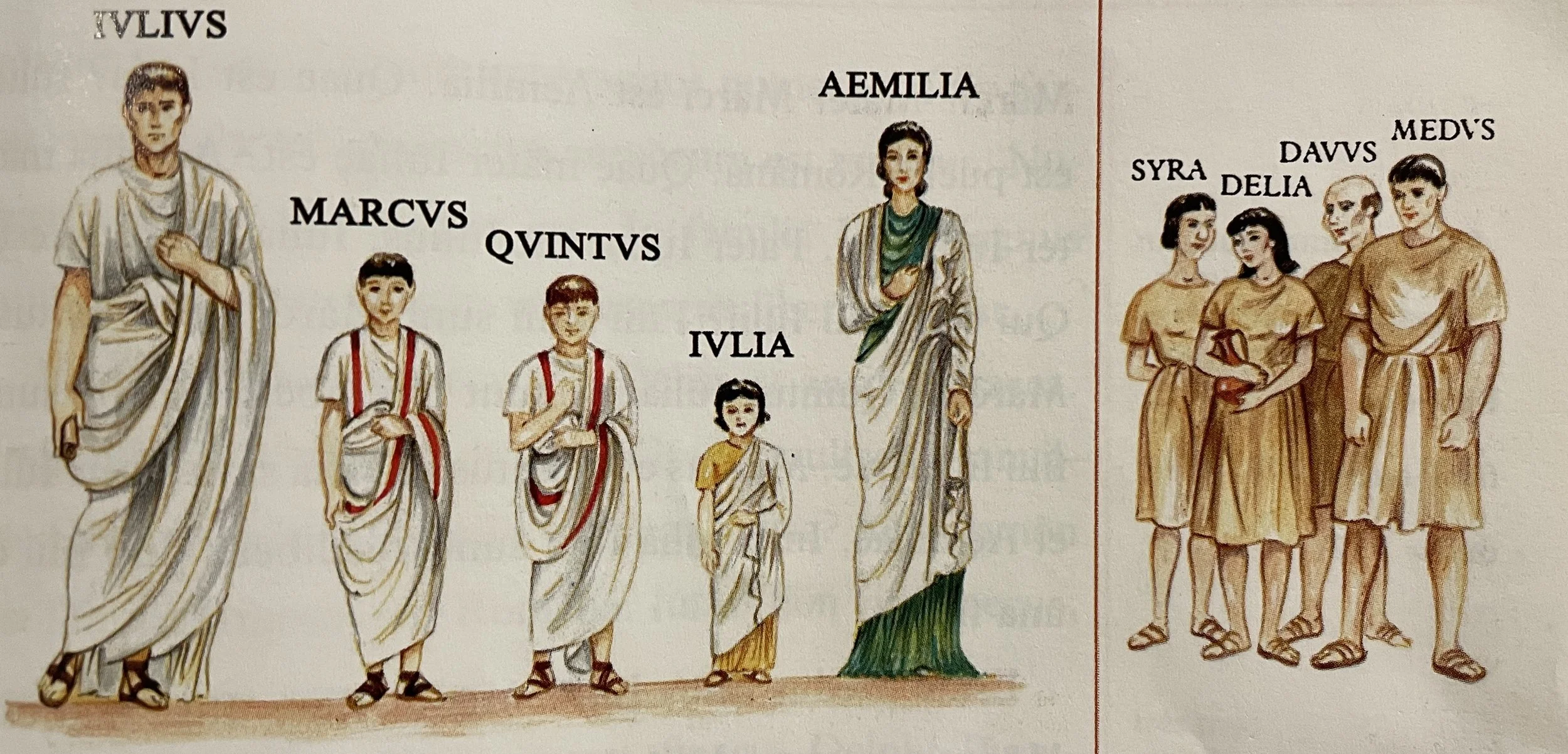

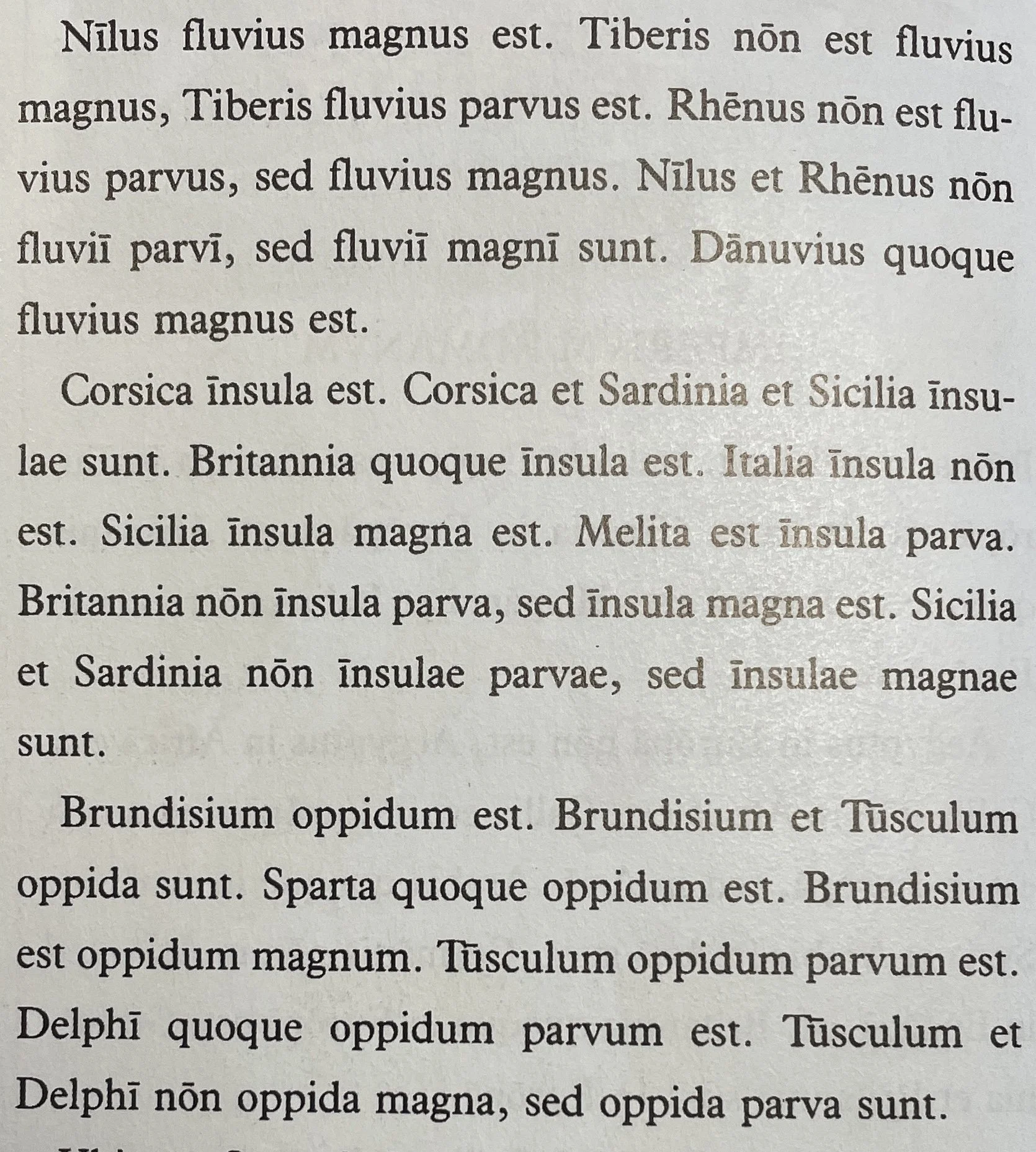

Lingua Latīna Per Sē Illustrāta : Capitulum Secundum : lines 35-36. To be fair to the publisher, after Capitulum Secundum extracts will not be given - you will need a copy of the textbook of your own.

Let’s practise the use of cuius with two more questions. Determine the answer to each one for yourself, before you reveal it. Please don’t take my very straightforward questions about human enslavement as any kind of comfort with this cruel and unjust practice.

-

Mēdus servus Iūliī est.

-

Dēlia ancilla Aemiliae est.

Satis est. Until next time.